As an indie effort it is reasonably short, comprising five game areas, but considering the overall setting is just an apartment building, and a destroyed one at that, each area has a distinct look and is gorgeous despite the desolation. For all the desolation, it’s a simply beautiful game to look at.

Starting a new game, then, you awake in a devastated room. This is a good thing, as some of the puzzles aren’t. It’s very accessible.Ī refreshingly no-nonsense title screen makes things easy. There is a single screen, with the controls keys (normal WASD) on the left load, new game and exit in the middle, with the helpful instruction you can save by sleeping and video options on the right. Homesick’s intention to not get in your way is apparent on the title screen. In other words, unlike Dear Esther, it’s actually a game, but manages to be a game without the clunky intervention of on-screen prompts or deus ex machina NPCs with convenient explanations and items. In many ways, it is more successful at what Dear Esther was created to achieve, because it has a strong but mostly inferred narrative, and while it is more conventionally a puzzle game, it manages to portray those puzzles and their solutions in a manner very integrated into the game world. This is important because comparing Homesick to Dear Esther is unfair.

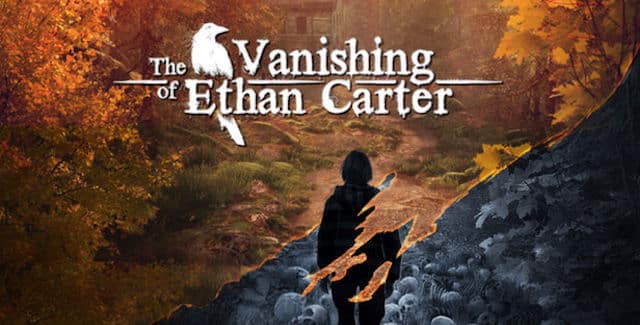

Partially visible clues allow you to deduce further actions, which in turn allows further progress. The Vanishing of Ethan Carter also had strong narrative with an unusual conclusion, but with puzzles to solve and areas to unlock along the way. But even its own creator has pursued interesting narrative in a more conventional interactive way for more commercial follow-ups like Everybodys Gone to the Rapture. I may be jumping to conclusions, but I think something has gone badly wrong….Ĭue some debate, so in that sense, it was a success. Where some games experiment with procedural generation of the environment, Dear Esther was an almost completely linear path around an island – what was random was the order in which you would hear the narrator’s fragmented memories, leaving the player (or “experiencer”) to draw their own conclusions about what happened. Dear Esther was an academic’s exploration of what constitutes a game. I think some understanding of what this might mean is important, not least as Homesick has been compared to Dear Esther (with one site waggishly deeming it “Fear Esther”).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)